By Keva Hoffmann Boardman —

I wake up in the morning and the first thing I do is pull up the weather app on my phone. I want to know temperature and precipitation possibilities in order to get dressed appropriately.

Humans have always watched the weather. Where to settle, when to plant and harvest, what to accomplish during the day and yes, how to dress are all dictated by weather. Weather encompassed the seasons of the year which could be wet or dry, hot or cold. Weather was either your friend or your worst enemy. It has always been watched, but it has not always been recorded on a daily basis and used to predict weather patterns, droughts and storms.

The science of meteorology, the tracking and understanding of weather patterns is really a relatively recent thing. Ancient Babylonians tried to predict major weather change based on the shape and look of the clouds. Egyptian astronomers were fairly adept at predicting the arrival of the Nile’s seasonal floods. Aristotle wrote Meteorologica as a compilation of all known knowledge about atmospheric phenomena, theories and guidelines for predictions. But it was the invention of data recording devices — barometers, dew point calculators, anemometers, hygrometers — that helped insure accuracy. Ordinary people, interested in the nature of weather, began keeping records. Well, not all were ordinary; Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo and Benjamin Franklin are on that list.

In the early 1800s, volunteer recorders and observers of weather in the United States started seeing patterns emerge in the data. The telegraph, invented in 1837, aided in weather information collection and sharing. In 1849, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, began collecting data from across the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean by giving out weather instruments. Weather watchers transmitted their observations to the Smithsonian at least three times a day. Weather maps were drawn, sent to press and posted in public places within about three hours. A six-word message relayed the city, barometric pressure, dew point, temperature, cloud cover, wind velocity and direction. As people daily transmitted weather information, scientists correlated and analyzed it to find the patterns and make predictions — modern meteorology was born.

One hundred fifty volunteer observers across the nation reported regularly to the Smithsonian. By 1860, that number had risen to 500. Texas had at least 42 men and women who were Smithsonian meteorological observers between 1854 and 1873. Several of these were well-known individuals in New Braunfels; two of them lived and worked here.

Louis Cachand Ervendberg, born around 1809 in Germany, emigrated to Illinois in the 1830s. He came to Texas in 1839, and after meeting up with Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels in Industry, Texas, he was given the job of pastor of the German Protestant immigrants. He and Ferdinand Lindheimer met the immigrants at Indianola and came inland with them. Ervendberg first lived in a house on Church (now Coll) Street, behind the log German Protestant Church. The cholera outbreak of 1846 was the cause of at least 60 orphaned children. The Ervendbergs opened their home and set up a tent to house and care for them. In 1848, Ervendberg set up the first state-sanctioned orphanage (Waissenhaus) out near Gruene.

Along with their own five children, the Ervendbergstaught roughly 20 orphans farming and housekeeping, as well as reading, writing and arithmetic. Ervendberg left the pastorship in 1851 and concentrated on finding out what crops could be grown in Texas. He experimented with different wheats, tobacco, medicinal plants, sheep and silkworms. Ervendberg corresponded with many men, including Asa Grey at Harvard. He was also one of the early Smithsonian meteorological observersof the 1850s. The rest of the Ervendberg’s story has been covered by Myra Lee Adams Goff in “Around the Sophienburg” articles (search on Sophienburg web site).

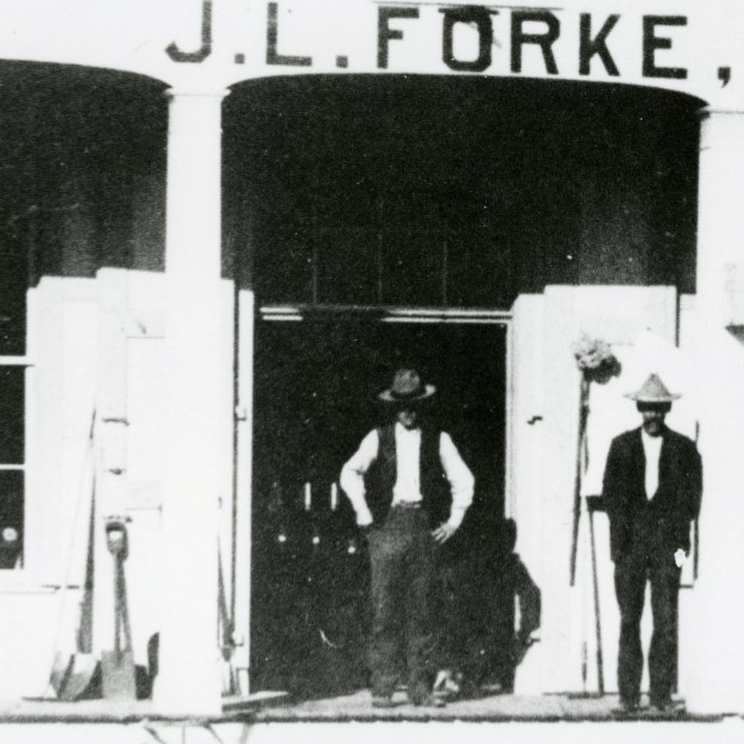

Jacob Ludwig Forke was born in 1817 in Hanover, Germany. After arriving in New Braunfels, he took over the position of Smithsonian meteorological observer reporting from 1855 to 1857, after Ervendberg left New Braunfels for Mexico. Family lore says Jacob made daily trips out to the Waissenhaus to record his observations. He married Karoline Langkammer, one of the orphans, in 1856. Talk about your “meet cute”!

Jacob Forke first farmed land on the Waissenfarm for at least a year, making 32 bushels of corn which was ground into meal. Eventually, wife Karoline bought the store and home of Victor Bracht (author of Texas in 1848) in 1865. The 1852 Bracht home and store stood at 593 S. Seguin Street, the present-day corner carpark of Bluebonnet Motors. Karoline deeded the property to her husband in 1866. No reason for this rather interesting chain of ownership can be found. However, a story has been told that Karoline would often leave her home and go next door to the Forke store to fuss at her husband and the men gathered inside playing skat or dominoes instead of working. She was obviously one of those strong, independent, no-nonsense German women. The property was sold by the Forke descendants in 1970, and eventually the store became a part of the New Braunfels Conservation Society’s Historic Old Town New Braunfels.

The telegraph had given meteorologists the ability to observe and display almost simultaneously all the observed weather data. This led to actual forecasting of weather. Because of the complexity of capturing and understanding the weather information, the system became part of a governmental agency. President Ulysses S. Grant signed a law in 1870 which birthed the first national weather service as a part of the US Army Signal Corps. In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison moved the meteorological responsibilities to the newly-created US Weather Bureau, an agency of the Department of Agriculture. The Bureau eventually became the National Weather Service, an agency of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in 1970.

Whether or not you are interested in weather, are you not continually amazed at how our little Hill Country town finds it way into the history of our world?

Sources: Sophienburg Museum: Oscar Haas Collection, Newspaper Collection, Forke and Ervendberg genealogies; PBS: The American Experience: A Brief History of the National Weather Service; National Weather Service: History of the National Weather Service; OpenMind BBVA: Meteorological Records: This Is How We Started to Record the Climate.